This is from the booklet The Inner Temple: A Brief Historical Description by J. H. Baker, K.C., LL.D., F.B.A. published in 1991 and some practices have changed since this booklet was published. For current practice see the Inn’s website.

The history of the Temple begins soon after the middle of the twelfth century, when a contingent of knights of the Military Order of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem moved from the Old Temple in Holborn (later Southampton House) to a larger site between Fleet Street and the banks of the River Thames. The new site originally included much of what is now Lincoln’s Inn, and the knights were probably responsible for establishing New Street (later Chancery Lane), which led from Holborn down to their new quarters. Following their custom, the knights built a round church patterned on the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. An inscription on the Round recorded that it was consecrated by the Patriarch Heraclius on 10 February 1185, in honour of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It is thought that King Henry II was also present on that day, inaugurating a long association between the royal family and the Temple.

Among the other buildings erected by the knights were dormitories, storehouses, stables, chambers, and two dining halls, one of them in the consecrated central portion and connected with the church by a cloister. It was a house fit for kings to stay in, and several did so. During a visit by King John in January 1215 he received a deputation of barons demanding a charter of liberties; and when the Great Charter was signed later in the year, the Master of the Temple was one of the witnesses. The knights took advantage of their special privileges to make their sanctuary a safe place for depositing treasure, and during the thirteenth century the New Temple became a busy financial centre. It was no doubt during this period that the first handful of lawyers came to live in the Temple, not as distinct societies but as legal advisers to a wealthy international organisation. The Templars thrived, adding to their round church a fine nave, which was consecrated in the presence of King Henry III in 1240. Many knights associated with the order were buried in the church, the most distinguished being William Marshal (d. 1219), first Earl of Pembroke and regent of England, the very model of medieval English chivalry, and one of the instigators of Magna Carta. Marshal’s armoured effigy, battered by time and war, may still be seen in the Round.

After losing the Holy Land in the 1290s, the order of the Temple fell into a decline. The knights were dubiously accused of improprieties, and in 1312 their order was dissolved. Although the pope granted their estates to the Knights Hospitaller of St John of Jerusalem, King Edward II seized the New Temple as forfeit to the Crown. Nevertheless, the consecrated portion was conceded to the Hospitallers, and the remainder was sold to them later.

It is unlikely that the Hospitallers occupied the Temple personally; it was merely a source of revenue. But it is equally unlikely that the Temple was let to lawyers as early as Edward II’s reign. The legal profession was still nomadic, and when in the 1330s it migrated en masse to York (with the central courts) the shopkeepers near the Temple complained of a sudden loss of income. The courts returned to Westminster for good early in 1339, and the inns of court as distinct societies probably date from the years immediately following that event. In that very year a man was killed in the Temple by a servant of the apprentices of the king’s court, which suggests that they may already have formed a community there. Ancient tradition dated the legal occupation of the Temple to the 1340s, and it was probably around that time that the outlying land along Chancery Lane – not being required by the lawyer tenants – was alienated to the bishop of Chichester to enlarge the site that later became Lincoln’s Inn. The exact date of formation of the inns of court and chancery will never be known. Unlike colleges at the universities, they were not incorporated or endowed by benefactors, and they did not acquire the freehold of their sites until much later. But it now seems likely that, from the beginning, there were two legal societies in the Temple: one (the ‘inner inn’) using the hall next the cloisters, and the other (the ‘middle inn’) using the unconsecrated buildings between the inner portion and the Outer Temple. A hall was necessary to an inn of court not merely for meals, but because the legal societies operated from their first formation as academic communities, with lectures and disputations. The two halls in the Temple would therefore naturally have attracted two inns. We do at least know for certain that the Inner Temple and Middle Temple were distinct communities by 1388, when they are first mentioned by those names in a manuscript year book.

Little is known of these fourteenth-century societies in the Temple. The best-known incident in their history was the sacking by Wat Tyler’s rebels in 1381, when some of the buildings were pulled down and lawyers’ records burned. The chroniclers of that melancholy event refer to ‘apprentices of law’ in the Temple, but give no details of the legal societies or their buildings. The devastation of 1381 may have been the occasion for rebuilding the Inner Temple hall. At any rate, the little hall which was demolished in 1868, though much altered over time, had a timbered roof of fourteenth-century style; it must therefore have been built by the lawyers rather than by their predecessors. Only five members of the Inner Temple before 1400 are known for sure, but they included the celebrated William Gascoigne, later chief justice of the King’s Bench (d. 1419), remembered by posterity for his judicial courage in committing Prince Henry (later King Henry V) for contempt. A less certain claim has been made for Geoffrey Chaucer, whose name a Tudor antiquary claimed to have seen in the Inn’s archives. Whether or not Chaucer was a member, he evidently knew the Temple well enough; his ‘gentle manciple . . . of a Temple’, portrayed in the prologue to the Canterbury Tales, served a society of ‘masters more than thrice ten’, and presumably a larger community of students.

The fifteenth-century Temple is almost equally obscure, since no domestic records survive for either society before 1500. Indeed, the only inn of court to possess records from the fifteenth century is Lincoln’s Inn, whose Black Books (beginning in 1422) provide most of our information about the daily life of the inns at this period.

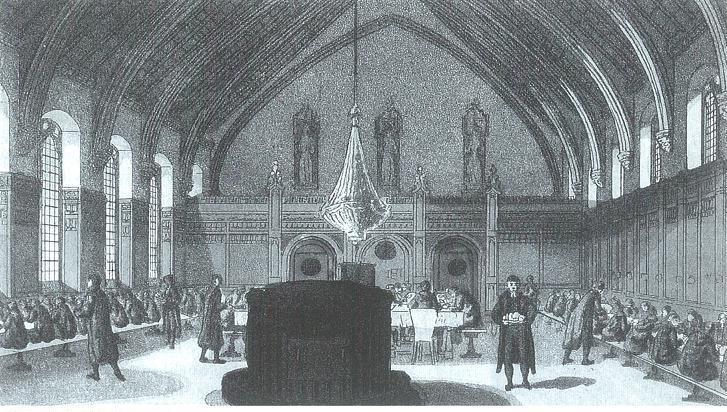

The majority of students were the sons of country gentlemen, not intended for the legal profession. The minority who pursued the severe study of the law were expected to keep the two learning vacations (Lent and Summer) each year, when courses of lectures were given on the old statutes, and also the more relaxed Christmas vacation, when a lord of misrule and his court presided over the festivities. In term-time the students attended Westminster Hall, to watch the courts in action, and throughout the year they took part in lengthy, intricate moots. For these vocational exercises, the hall of each inn was arranged to resemble a court, with a bar and bench. A young student sat inside the bar as an ‘inner barrister’; when he became suitably qualified to argue points of law, he was called to the bar, and as an ‘utter barrister’ stood outside the bar at moots. In due course a barrister would be expected to deliver a lecture (or ‘reading’), after which he sat on the bench at moots as a ‘bencher’. These degrees achieved public recognition in the sixteenth century; but they have remained to this day inns of court degrees, referring to the bar and bench of the inns rather than of the courts. We know from scattered references that the Inner Temple had the same system in the time of Edward IV. The first identifiable Inner Temple reading now surviving was given by Thomas Welles in 1460, though Thomas Littleton is said to have given one before 1453. Thomas Welles is also mentioned as Treasurer in 1484. The first reference to a ‘bencher’ by that title is to one Baker in the 1470s or early 1480s, and the first to a ‘barrister’ is to John Green in 1481.

Like the other inns, the Inner Temple seems in this period to have developed its own geographical catchment areas; whereas the Middle Temple was dominated by west countrymen, the Inner Temple drew more from the north, the midlands, and London. It is notable that Richard III’s principal lawyers were all Inner Templars: Sir William Catesby (beheaded in 1485), chancellor of the Exchequer and speaker of the Commons, Sir Morgan Kydwelly (d. 1505), attorney-general, Thomas Lynom (d. c. 1518), solicitor-general, and Thomas Kebell (d. 1500), attorney of the Duchy. Other alumni included John Paston (d. 1466), who lived in the Inn for twenty years and mentioned it in his letters, Sir Thomas Littleton (d. 1481), renowned author of the Tenures, and Sir Richard Sutton (d. 1524), founder of Brasenose College. Two of the earliest named law reporters (John Caryll and John Port) were also Inner Templars.

The sixteenth century was an age of expansion for the common law and its practitioners, and all the inns were substantially enlarged and beautified during the Tudor period. Spenser was referring to the Temple when he wrote in Prothalamion (1596) of ‘. . . Those bricky towers, the which on Thames broad aged back doth ride, wherein the studious lawyers have their bowers, And whilom wont the Templar knights to bide . . .’. The characteristic brick of the late Elizabethan Temple must have represented, for the most part, recent construction. Some of the development may be traced through the Inn’s records, since the minutes of parliament (the governing body of benchers) exist from 1505; but most building projects were carried out with private money, the investors retaining a freehold interest in the chambers. Very few of these Tudor buildings survived into the nineteenth century, though the name Hare Court still commemorates a rebuilding scheme financed by Nicholas Hare in 1567. In Hare’s time there were 100 sets of chambers in the Inn, making it the second largest (after Gray’s Inn); in 1574 it is recorded that only 15 benchers and 23 barristers lived in, well outnumbered by the 151 resident students. Celebrated alumni from this period included Sir Thomas Audley (d. 1544), the Inn’s first lord chancellor, two subsequent holders of the great seal (Sir Thomas Bromley and Sir Christopher Hatton), and, above all, Sir Edward Coke (d. 1634). Coke is still remembered for his Reports and Institutes, which included a Commentary on Littleton; but perhaps the greatest achievement of his stormy judicial career was the foundation of English administrative law.

Coke’s career leads us into the seventeenth century; although he left the society on becoming a serjeant in 1606, he was allowed to retain chambers in his beloved Inner Temple until his death, and must have been a dominant presence. The expansion of membership continued throughout that period: over 1,700 students were admitted to the Inn between 1600 and 1640. In 1642, however, the news of Edgehill sent bench and bar rushing home. The Inns were all but closed for four years, and the legal university suffered a mortal collapse. Readings were discontinued, and their revival after the interregnum was short-lived. The first Restoration reading (by Sir Heneage Finch in 1661) was a magnificent occasion. King Charles II attended the reader’s feast in person, and the Duke of York (later King James II) became the first royal bencher. But readers in general found it was easier to pay the fine for default than to prepare lectures and pay for feasts, while the Inn doubtless concluded that monetary compensation was more useful than specific performance.

Readings therefore petered out in 1678. (The Inn has nevertheless continued to elect readers, this being the sole qualification for having one’s coat of arms erected in hall; in recent times the Reader has normally held office for the calendar year prior to becoming Treasurer.)

In the Restoration period the Inn suffered three serious fires, affecting mainly the northern and eastern parts, and in consequence rebuilt Hare Court, Tanfield Court and King’s Bench Walk – now the oldest range of chambers still in use in the Inn. Distinguished alumni included John Hampden (d. 1643), opponent of ship-money, John Selden (d. 1654), legal historian and defender of English liberties, Henry Rolle (d. 1656) and Sir John Vaughan (d. 1674), two very learned chief justices, Lord Nottingham (d. 1682), the ‘father of modern equity’, and the notorious ‘Judge Jeffreys’ (later Lord Chancellor Jeffreys, d. 1689) of the Bloody Assizes.

Image copyright © The Inner Temple

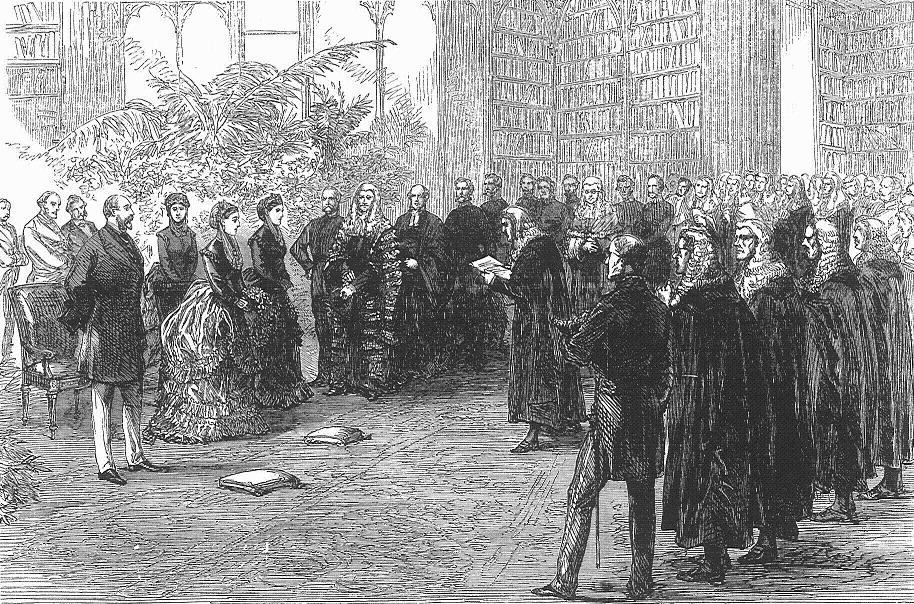

The eighteenth century was an era of greater stability, perhaps of genteel decline. Charles Lamb, who was born in Crown Office Row in 1775, painted a loving picture of the Temple of his youth in his essay ‘The Old Benchers of the Inner Temple’. If he is to be trusted, the late-Georgian benchers were a very singular body of individuals. Sir Joseph Jekyll, Treasurer in 1816, similarly wrote of his elderly fellows as ‘fogrums’ opposed to all modern fashions, including new-fangled comforts. The decrepit state of some of the benchers was matched by that of the gloomy alleys and decaying buildings. Charles Dickens (Pickwick Papers, ch. 31) wrote of the Temple’s sequestered nooks, comprising for the most part ‘low-roofed, mouldy rooms, where innumerable rolls of parchment, which have been perspiring in secret for the last century, send forth an agreeable odour, which is mingled by day with the scent of the dry rot, and by night with the various exhalations which arise from damp cloaks, festering umbrellas, and the coarsest tallow candles’. Much of the Inner Temple was rebuilt between 1830 and 1900, replacing Restoration elegance and Dickensian quaintness with Victorian stolidity. The most successful of the rebuilding projects, though it resulted in the demolition of the little fourteenth-century hall, was the new Hall and Library, designed in a perpendicular style by Sydney Smirke and opened by Princess Louise in 1870.

Eminent Inner Templars from these centuries included a prime minister (George Grenville), seven lord chancellors (Lords Harcourt, Macclesfield, Talbot, King, Bathurst, Thurlow, and Chelmsford), Lord Ellenborough, Chief Baron Pollock, Lord Bramwell, James Scarlett (later Lord Abinger), Daines Barrington (author of Observations on the Ancient Statutes), John Austin (the legal philosopher), Henry Hallam (the constitutional historian), Sir Edward Hyde East (author of Pleas of the Crown), Dr Lushington, and Sir James Stephen.

The last hundred and fifty years have brought significant changes in the size and composition of all four inns of court. The membership was widened to include law students from every corner of the empire, and (after 1919) women; the first woman barrister (Ivy Williams) was called to the bar by the Inner Temple in 1922. The number of benchers has risen from around 30 (Chaucer’s number) in 1850 to over 200 in 1990.

The twentieth century also brought the catastrophe of war to the Temple. Not only did many members lose their lives in the services during two world wars, but in 1940-41 almost half the Temple was demolished by bombing.

In the Inner Temple alone the air raids destroyed Fig Tree Court (1666 and later), four buildings in King’s Bench Walk (1677 and later), Inner Temple Cloisters (1681), Crown Office Row (1737, 1864), 2 Mitre Court Buildings (1830), Harcourt Buildings (1833), the Hall and Library (1870), and Tanfield Court (1881). They also destroyed the Master’s House (1667), and much of Temple Church, owned jointly with the Middle Temple.

Some of these buildings were restored after the war to their original appearance, but the devastation also provided an opportunity to enlarge some of the courts. The narrow Fig Tree Court disappeared, being incorporated into Elm Court as part of the Middle Temple; and the decision was taken to achieve a spacious Church Court by resiting Lamb Building, which had stood in its centre. The vista from the Gardens, between Harcourt Buildings and the Library, was completely redesigned in a Georgian style (in red brick faced with stone) by Sir Edward Maufe and Sir Hubert Worthington.

Next chapter: The Constitution of the Inn