Once more the Library was rebuilt and was in use again by 1680, the upper room still being used for social functions, the drinking of wine by members after dinner and the serving of suppers to the invited guests of the Masters of the Bench. Of its administration during the 17th century little is known. There was, apparently, no catalogue, certainly no official library keeper, and no rules existed to govern the use of the material and the conduct of readers. Then in 1707 the Inn was offered what has since become known as the Petyt MSS. William Petyt, Treasurer of the Inn in 1701-2, was for many years Keeper of the Records in the Tower of London. He had antiquarian interests, was a scholar of some distinction and, despite later tales to the contrary, was a scrupulously honest collector of ancient documents. At his death he left to the Inn a great mass of manuscripts together with a sum of money to construct a building to house them. By his bequest, which was accepted, he performed a double service, that was to be of lasting benefit. He provided the Inn with a manuscript collection of a richness which few private societies could otherwise have hoped to obtain; and this in turn provided the spur for the reorganisation of the Library upon a sound administrative basis. His collection, still intact after almost three hundred years, contains 386 volumes and covers a diversity of subjects.

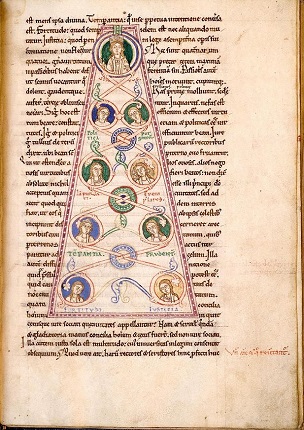

These include Year Books, Registers of Writs, Statutes, Legal Treatises, Precedent Books and Commonplace Books. Among chronicles there is an uncollated early 13th century manuscript of Roger de Hoveden’s Historia Anglorum, which once belonged to the Abbey of Rievaulx. There is also a long range of Journals of the House of Commons, some of which contain entries which were no longer decipherable when the printed version of the Journals was made. Among noteworthy manuscripts there is an early 12th century Macrobius, and the earliest known Books of Forms in Ecclesiastical Causes, from the end of the 13th century. There are works by Sir Francis Bacon, Sir Robert Cotton and Sir Thomas Bodley, and important original letters from such personages as Lord Burghley, Sir Edward Coke and Sir Christopher Wren.

Image copyright © Ian Jones

Items of interest include an original letter of Lady Jane Grey, signed by her as `Quene’, the original draft of Sir Edward Coke’s 12th and 13th Reports, and a Year Book for a term of Edward I, which seems to be contemporary and which is, besides, unique. There are also autograph letters by Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth I.

By 1709 the new Library had been built. It included the two former rooms (one of which was to be known as `the back library’) as well as a new room spacious and handsome. Samuel Carter, an `aged and impecunious barrister’ was appointed as Library Keeper to attend in the Library as follows: Lady Day to Michaelmas, 9.00am – 12.00, and 3.00pm to 6.00pm; Michaelmas to Lady Day, 10.00am to 12.00, and 3.00pm to 5.00pm. His salary was £20 a year. He it was who did the first work on Petyt’s books and manuscripts. He produced, besides, a draft catalogue of the books in the Library, dated 1713, which is still extant, but he died the same year leaving it unfinished. He was succeeded by Joshua Blew, a butler in the Inn, who served for fifty years as Librarian.

On 18th May 1716-17 a Bench Table Order was issued: “No copy or transcript is to be taken by any person of any manuscript books in the Library, and no books to be delivered or taken out of the Library without leave of the Table. This order to be hung up in the Library”. Thus was formally established the principle that the Library was essentially for reference and not for borrowing. But though the books were now housed either in close presses or frames with wire guards the manuscripts seem to have been easily available (at least to Masters of the Bench) and were as often consulted out of curiosity as out of need; their availability not being restricted in the modern sense until late in the nineteenth century. If in the early days the Library’s acquisition of books had been haphazard it was regulated by a Bench Order of 1713 directing the Treasurer to expend £20 a year on books, but it was the Librarian, Joshua Blew, who was responsible for the actual purchase of books, often their selection too, their binding, and on occasion, the publication of the manuscripts. During his years in office he produced four catalogues. These are notable for the careful and accurate annotations to entries, for Blew had all the instincts of a good bibliographer.

In the eighteenth century the great majority of books purchased were law books; of the books presented the majority were also law books. But antiquarian, historical and literary interests were also held by the members of the Society, and the purchase or presentation of books reflected these interests as is duly recorded in the catalogues subsequently to be issued.

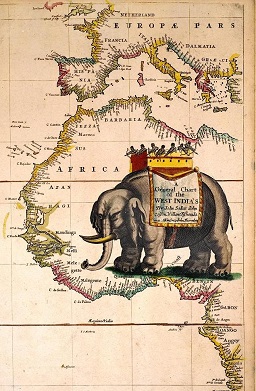

This diversity of interests, continued to the present though in modified form, explains the presence today of many valuable works, all either original or second editions: Higden’s Polychronicon, Strutt’s Sports and Pastimes (1810), Hakluyt’s Voyages (1598-1600), Clarendon’s History (1702-4), Saxton’s Atlas of England and Wales (1579) and, Seller’s Atlas Maritimus 1678. The list of incunabula acquired is shorter but includes The Nuremberg Chronicle (1493), volumes of statutes printed by Caxton in 1490, as well as two out of the three volumes of statues issued by Machlinia, the first of the English law printers. On the whole however the purchase policy towards legal and allied materials was highly selective, and books had to prove themselves before they were bought. The forty eight titles purchased in 1723 range in publication date from 1651 onwards but only four of these were current publications.

Many problems familiar to modern librarians were already being encountered. By 1729 as a result of gifts the problem of duplication existed and the Librarian drew up a list of seventy nine titles for disposal by sale. Books were being supplied by mistake and having to be returned, whilst overcharging of bookseller’s accounts was not uncommon.

The catalogue of 1773, the work of another Librarian, the Rev. William Jeffs, was the last to be in manuscript and was the most scientifically planned to date. It was ordered that “The Librarian … to make a complete Catalogue of all the books in the Library and to range the books relating to the several subjects they treat upon in distinct presses so as to compose a separate Library of Law and Equity, Civil Law and Parliamentary proceedings, Classics, General and Biographical History, Theology, Heraldry, Physic, Miscellaneous Books or others relating to any particular science or subject and manuscripts; that in the Catalogue to be made there shall be one column to signify the number of the press, another the shelves, another the name of the book, another the name of the printer and another the date of the year, and that the books may follow in an alphabetical manner, as much as may be, and that all duplicates may be placed together in two or three presses, and that the same may be completed by the first full week in Michaelmas term, and for which this Society do desire his acceptance of ten guineas.”

In 1784 Randall Norris, a clerk in the Treasurer’s department (he subsequently became Sub Treasurer) was appointed Librarian, and it was during his tenure of office that the earliest printed catalogue, dated 1806, was issued. The surviving evidence suggests that the appointment of Norris was not a happy one. His intellect was not powerful and he possessed none of the qualities that make a true librarian. When he died in 1827 Charles Lamb wrote a famous letter about him to Crabbe Robinson: “In him I have a loss the world cannot make up. He was my friend, and my father’s friend, all the life I can remember. I seem to have made foolish friendships ever since … To the last he called me Charley. I have none to call me Charley now. Letters he knew nothing of, nor did his reading extend beyond the Gentleman’s Magazine. Yet there was a pride of Literature about him from being among books (he was Librarian) and from scraps of doubtful Latin which he had picked up in his office of entering new students, that gave him very diverting airs of pedantry. Can I forget the erudite look with which, when he had been in vain trying to make out a black letter text of Chaucer in the Temple Library, he laid it down and told me that “in these old books, Charley, there is sometimes a deal of indifferent spelling”, and seemed to console himself in the reflection”.